by Iris Milligan

Nature often inspires innovation, with many of us looking to the natural world for solutions in our studies and beyond. This approach is known as biomimicry, and it’s commonly used in fields like architecture and structural engineering. For example, researchers have studied dragonfly wings for their unique design (cells by the name of nanopillars), which naturally prevents bacteria from attaching to the surface. This is also the case for Velcro, which was invented by Swiss engineer George de Mestral in 1941 after he removed burrs from his dog.

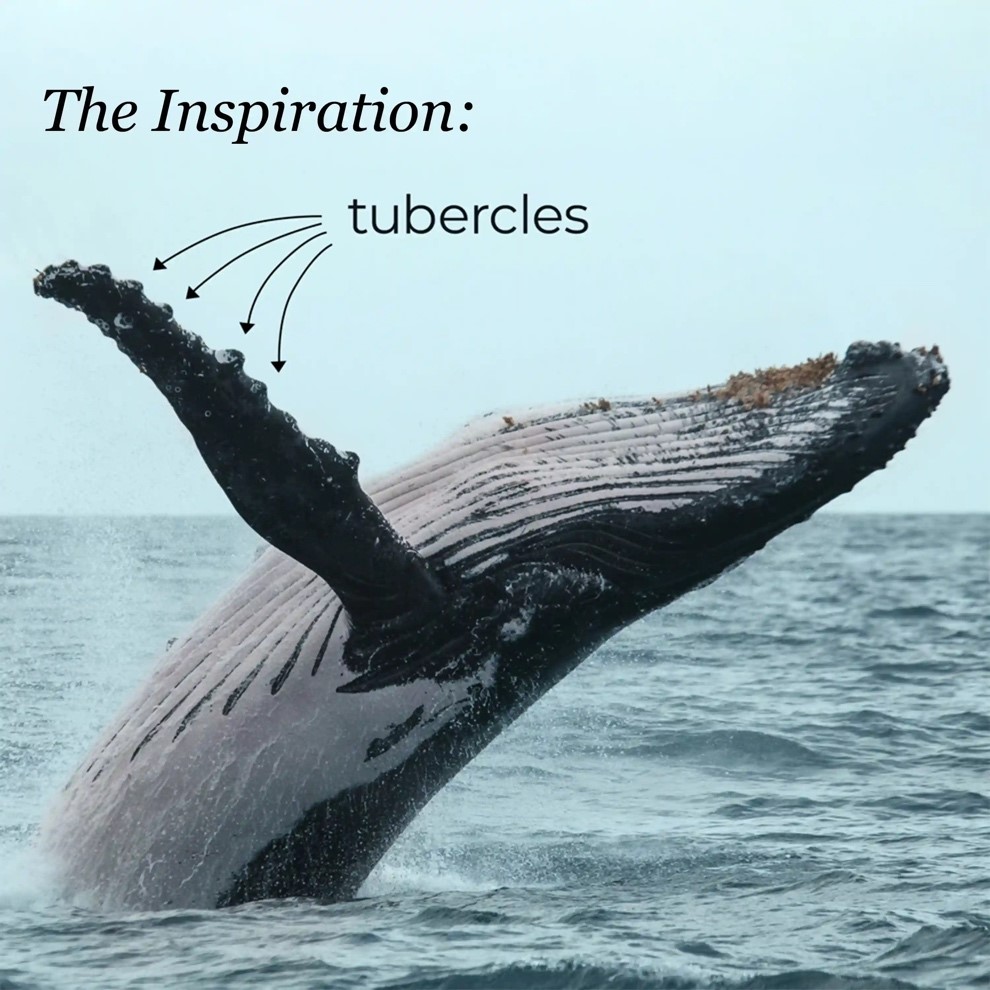

This research can be applied to not just the terrestrial realm but also the aquatic environment. We have already started this with Sharkskin-inspired swimsuits and tubercles for wind turbines. Marine mammals are similarly inspiring, such as with their blubber, which not only keeps them warm in frigid oceans but also acts like a natural buoyancy aid, allowing them to float effortlessly. Or their sheer sizes, with hearts so large they could fill a car and lungs capable of holding enough oxygen to dive deep for up to 120 minutes.

Humans have been able to train their bodies to hold their breath, with the longest hold being 24 minutes. Additionally, their ability to not only survive being deeply wounded by the propeller of a boat but heal within a few months—with nothing more than a scar—has been observed in several species. I doubt I would survive something like that without medical attention.

Before starting my PhD on wound healing in marine mammals I was aware of the basic injuries they suffer, but that they can heal and recover from even the most extreme damage shows how extraordinary they are.

Marine mammals have nailed life in the water, showing off some wild adaptations that let them dominate in harsh ocean environments. Low oxygen, high salinity, and freezing temperatures are just a few things they endure. Studying how marine mammals heal from such severe wounds could potentially revolutionize medical treatments for humans. By understanding the biology and mechanisms behind their remarkable recovery, we may uncover new ways to treat trauma, heal wounds faster, and even tackle bacterial resistance.

By imitating nature’s designs—whether it’s for improving materials or healing wounds—we can open new frontiers in science and medicine. After all, nature has had millions of years to perfect its designs, and by studying and emulating them, we’re simply giving credit where it’s due. As the saying goes, imitation is the best form of flattery.