by Patra Petrohilos (PhD Student)

I love dystopian horror. I love to relish in the thrill of disgust from the comfort of safety – a comfort bolstered by the knowledge that such grotesquerie could never actually happen in real life. Zombies don’t exist. Monsters aren’t trying to escape from the underworld. Cancer isn’t contagious. Actually, maybe scratch that last one. . .

You see, nature may not have the imagination of Stephen King, but it does have something even more powerful in its arsenal: mutations. Mutations are to evolution what creativity is to horror writers – the raw material that allows them to conjure up new and wondrous forms. From the most beautiful (buttercups, butterflies, butter yellow bumblebees) to the most horrific (flesh eating bacteria, pandemic inducing viruses, cancer cells).

Evolution favours the fittest individuals, be they butterflies or bacteria. In this case, “the fittest” just means the ones that are most successful at reproducing. If we are talking about koalas, reproduction means making cute little baby koalas. Everyone likes those. But when we’re talking about cancer cells, reproduction means growing and spreading and killing one’s host. Nobody likes that. Even the cancer cells probably wouldn’t like it – because killing their host also means killing themselves in the process. Kind of like a suicide bomber without the political motivation. But evolution is blind to morality and selects for the cute little baby koalas and murderous cancer cells equally – whatever is most efficient at making more copies of itself. Survival of the fittest.

Mutations are constantly arising in nature. Sometimes these make more successful versions of things, sometimes less successful. It’s a bit of a trial-and-error process. And somewhere in that trial-and-error process, a handful of cells have stumbled across the secret to become the most successful cancer cells ever. Super-cancers! How? By finding a sneaky way around that whole unfortunate dying-when-your-host-dies bit.

They do this by taking a leaf out of the life history book of parasites. Like cancer cells, many parasites are reliant on a host to survive. But unlike cancer cells, many parasites have the power to survive the death of their host by simply finding a new host – a power that evolution has also bestowed upon these super-cancers.

Yes, nature has managed to take one of the most awful diseases known to humanity and done perhaps the only thing that could make it worse. It has made it contagious.

Thankfully, such contagious super-cancers are mercifully rare and none of them affect humans (yet). But the rest of the animal kingdom has not fared quite so well. Leukaemia cells drift through the sea like hidden assassins, spreading from one unsuspecting clam to the next. Dogs can get mushroom shaped tumours on their penises from sex with a poorly chosen partner. And one of our most iconic Australian animals, the Tasmanian devil, is at risk of extinction from not only one but two contagious cancers (creatively named Devil Facial Tumour Disease 1 and Devil Facial Tumour Disease 2). Sometimes lightning really does strike twice.

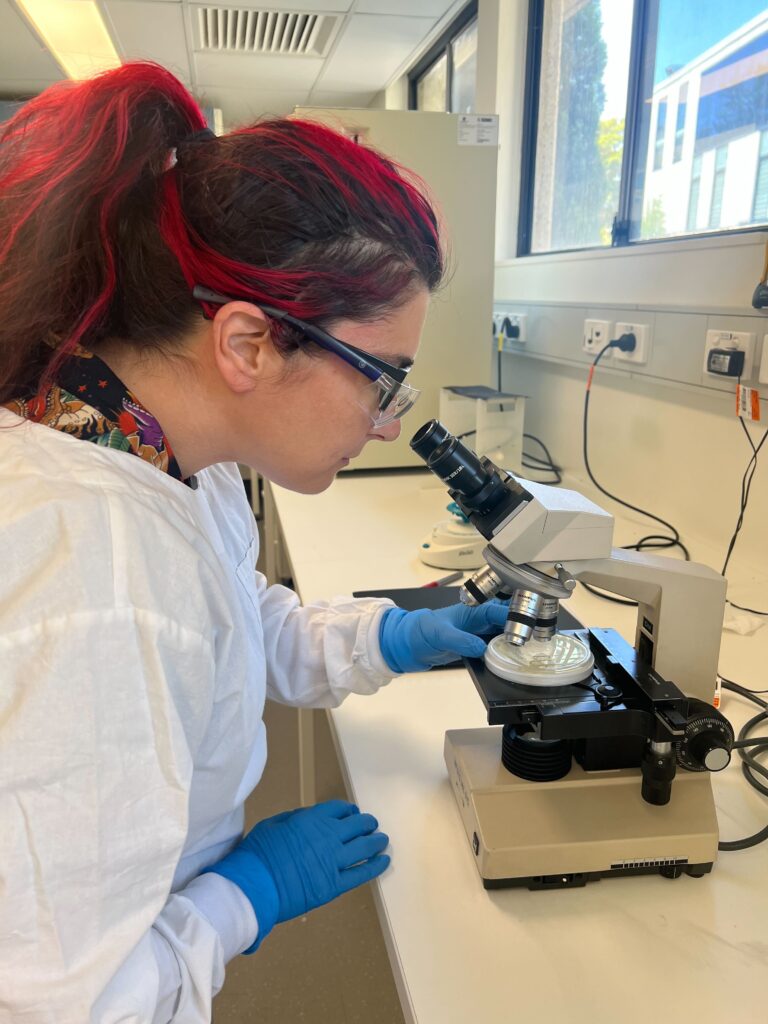

The good news is, this is where we come in. By researching Devil Facial Tumour Disease – one of the most uniquely horrifying and bizarre diseases to ever arise – we aim to understand how it works, how it spreads, how it evolves and, hopefully one day, how we can stop it.

Follow me for more fun and uplifting facts about the animal world!

Author:

Patra Petrohilos (PhD Student) is researching the evolution of devil facial tumour disease (DFTD). By investigating anticancer properties of naturally occurring peptides, she is aiming to identify novel agents with therapeutic potential against DFTD. Patra Petrohilos is a PhD student with the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for Innovations in Peptide and Protein Science (CIPPS). Follow their exciting research at https://cipps.org.au.